Happy Holidays! 15% OFF and FREE SHIPPING all ONLINE purchases over $60!

***Use Code: HOLIDAYS2024 at checkout***

(free shipping valid only within continental U.S.)

Menu

-

- Home

-

About Us

-

The Approach

-

Linking Language & Literacy

-

MindWing Learning

-

Learning Resources

-

SHOP

-

Blog

-

- About MindWing

- Our People

- Contact Us

- Your Account

- Login

-

United States (USD $)

Happy Holidays! 15% OFF and FREE SHIPPING all ONLINE purchases over $60!

***Use Code: HOLIDAYS2024 at checkout***

(free shipping valid only within continental U.S.)

Narrative is “Having a Moment” in Research Circles

by Sean Sweeney July 28, 2014 4 min read

This post is the fourth in our SGM® Summer Study Series. We and guest bloggers have been sharing research articles with connections to the methodologies of Story Grammar Marker®, Braidy, the Storybraid® and Thememaker®. The purpose of this series is to provide ideas and support for using our tools and expand your thinking during these summer months!

Narrative seems to be “having a moment” in research circles, with a number of recent articles being published related to the why and how of developing storytelling skills. One of the most exciting pieces is “Classroom-Based Narrative and Vocabulary Instruction: Results of an Early-Stage, Nonrandomized Comparison Study,” (Gillam, Olszewski, Fargo & Gillam, 2014) detailing a study primarily conducted by Utah State University and published in Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools (and available to ASHA members in full text here).

This study com-pared the results of narrative and vocabulary instruction via a traditional versus an experimental approach in two first grade classrooms.

We’d encourage you to read the entire article as part of your “summer studies,” and it would be a great context for a discussion session among colleagues when you return to school in the fall, but some of the main points are as follows:

- The authors summarize recent research in the areas of narrative intervention, vocabulary in-struction and service delivery, providing helpful additional references supporting your strategies and use of SGM®. Of particular interest—this study was the first to examine the efficacy of in-class service delivery by a speech pathologist in the area of discourse or narrative instruction.

- As a curriculum tie-in, Narrative Elaboration Treatment or NET, in which students used story grammar cue cards to organize retellings, was cited as effective in helping them recall a history lesson placed in narrative form.

- 43 students in two classrooms were first assessed using the Test of Narrative Language (TNL; Gillam & Pearson, 2004) and placed in high- and low-risk groups. The classrooms then conducted a series of lessons for 30 minutes, three times a week over six weeks. The experimental classroom focused on specific narrative instruction led by an SLP and facilitated and carried over by the classroom teacher, while the comparison group was assisted by an under-graduate SLP student along with the teacher to maintain the same adult-to-student ratio.

- The comparison class used common comprehension instruction strategies regarding present-ed stories: think-alouds, visualization, beginning-middle-end story mapping, summarization, dramatization, and answering questions.

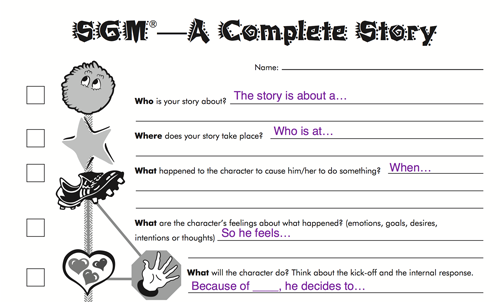

- The experimental class explicitly taught story grammar elements, particularly “complicating actions” or initiating events, and allowed for extensive practice in generating and analyzing narratives using an icon-based scaffolding system. In particular, the students were facilitated in using causal and other connections between story elements to formulate more complex sentences and narratives. The vocabulary instruction involved teaching words in the context of narratives.

- Results indicated clinically significant improvement on measures of narrative complexity and vocabulary knowledge after receiving the whole-class narrative instruction, while the narrative and vocabulary skills of the children in the comparison classroom remained the same. Analyses of improvement in even the low-risk group suggest that an “instruction program provided to an entire class of first graders by an SLP is very promising for improving the complexity of children’s stories.”

The results of the study indicate that it is definitely one for your Evidence-Based Practice file around your instructional tools, particularly SGM®! Although the specifics of some of the instruc-tional practices, for example the nature or type of the icons used to prompt story grammar ele-ments are not detailed here, it is quite easy to see the connections with the Story Grammar Marker methodology. The article also has implications for how we might go forward in using SGM® most effectively.

Service Delivery

When working in public schools and even now as a consultant, I have always been an advocate for whole-class instruction in tools that would benefit an entire class, and SGM has been a consistent presence in these lessons over the years. The study supports specific narrative instruction as beneficial to all students in a classroom; this research would be on point in discussions with reluctant principals or teachers who may think your push-in therapy is detrimental to “time in learning.”

Fostering Connections between the Story Elements

This study showed that repeated and frequent modeling and practice in retelling and generating stories while linguistically connecting story parts was more effective than traditional methods (e.g. wh- questions) in the comparison classroom. This can shape how we use SGM, as many clinicians and students can get stuck in a simple-sentence mode that sounds like this: “The character is….The setting is…The kickoff is…” While this is indeed a good step in comprehension and use of story elements, students benefit from focused modeling of the connections and cohesive ties that can be used to make a story map sound more like a real story!

One step I have found effective in making this transition to complexity is to write key connecting words on story maps to provide a visual scaffold, as in this example. Different key words and cohesive ties can of course be used and modeled!

This particular area of the study also reinforces the features of the SGM® iPad App, which, rather than allowing for recordings of students describing each narrative element individually, facilitates a visually supported—by the SGM® icons—recording of a complete story with all the connections between the elements. The students’ ability to then hear the story aloud provides an additional model and reinforcement!

Listening for the “Meta”

One other aspect of the classroom instruction involved students listening to classmates’ narratives and “marking off on bingo cards” the story elements they heard addressed within the narrative. While this could be achieved with other MindWing products such as the Universal Magnet Set, one of my favorite hands-on narrative tools, this suggests another activity that could be completed with the SGM® App. Because individual icons can be added to the Reporter’s Note-book, children could be engaged in doing this receptively as they listen to others’ stories, thus keeping all engaged!

References:

Gillam, S.L., Olszewski, A., Fargo, J., Gillam, R.B. (2014). Classroom-based narrative and vo-cabulary instruction: Results of an early-stage, nonrandomized comparison study. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(3), pp. 204-219.

Sean Sweeney

Sean Sweeney, MS, MEd, CCC-SLP, is a speech-language pathologist and technology specialist working in private practice at the Ely Center in Needham, MA, and as a clinical supervisor at Boston University. He consults with local and national organizations on technology integration in speech and language interventions. His blog, SpeechTechie (www.speechtechie.com), looks at technology “through a language lens.” Contact him at sean@speechtechie.com.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.