...FREE U.S. SHIPPING for orders over $60...

Menu

-

- Home

-

About Us

-

The Approach

-

Linking Language & Literacy

-

MindWing Learning

-

Learning Resources

-

SHOP

-

Blog

-

- About MindWing

- Our People

- Contact Us

- Your Account

- Login

-

United States (USD $)

...FREE U.S. SHIPPING for orders over $60...

Oral Language and Trauma: “Nobody Made the Connection”

by Maryellen Rooney Moreau August 14, 2019 6 min read

Personal Comment:

Map of MindWing’s upcoming travel.

Many emails come across our computers daily but sometimes it is a title that captures one’s interest. Today it was “Nobody Made the Connection” (Hughes, 2012, 2017). While preparing for a family vacation to Cape Cod, I came to the office to work on several impending workshops taking us at MindWing from workshops in Massachusetts, Maryland, Florida, and Hawaii in the next month.

We made it to The Cape! Maryellen Moreau and husband Gerry and their grandchildren.

All of these workshops have a social communication component in addition to the need for oral language narratives as a base for literacy. The title above is exactly what we are attempting and intending to do! Make the oral language, particularly the narrative language connection, to vulnerable children in our care.

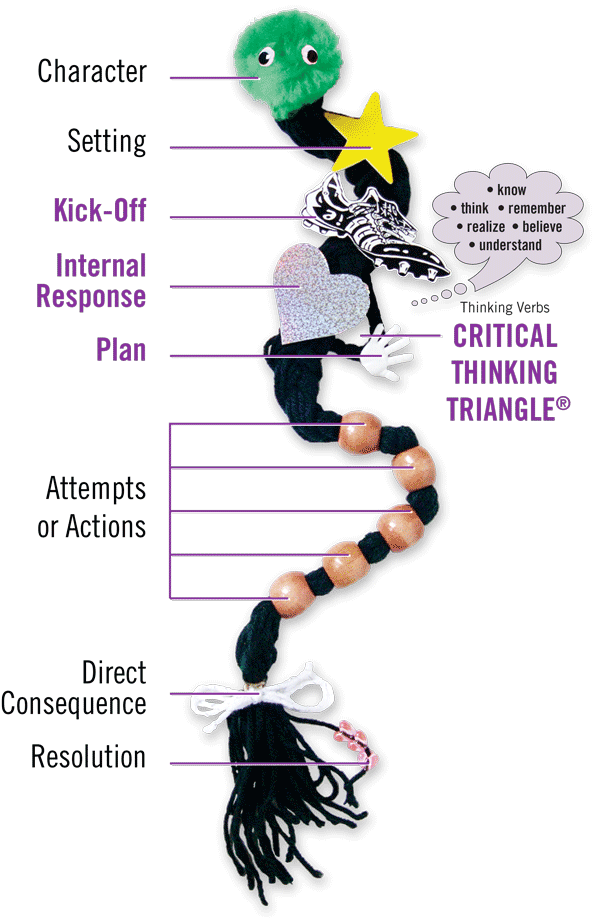

The ability to tell one’s own personal story, independent of prompting by others is of vital importance to children (and adults, for that matter!) throughout the world. The Story Grammar Marker® tools and approach serve this purpose: hands-on, self-cueing, icon-based system, multisensory in construct, following evidence-based social communication focus as well as application to academics in the areas of oral language, retelling, and writing!

Why is the social communication application of the SGM® so important?

At MindWing, we are presenting our tools for use in many school systems this summer to make this connection. From Maryland to Hawaii, to New Zealand and back to Florida, there is a great need voiced for help for students experiencing social communication difficulties.

Some of these students have experienced trauma where the response to “What happened?” is often “fight, flight or freeze.” Narrative ability is a vital oral language development skill, necessary for academic and social success.

Today, I received an email from MST Services, Youth Justice News at a Glance (Charleston, SC. 29407). The article was written by Dr. Jessica Edwards and was posted on the website of The Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health in 2018. The title is “Language impairment needs more recognition in the juvenile justice system.”

Coincidently, this article ties into MindWing’s requests for presentations on narrative development, which is the point that vocabulary words and sentences are connected to form stories. (Please see the work of Pamela Snow on this narrative need, referenced below.)

The reason for writing at this time is that the article cites a 2017 study of 93 young male offenders in a secure custodial facility in the UK by Nathan Hughes. This study resulted in the following outcomes stated by this quote:

“Despite >40% of those with language impairments previously being involved in the care system or attending a specialist school, the majority had not accessed any form of speech and language therapy prior to custody.”

“These findings identify that access to speech and language services in severely limited in young offenders.”

“The researchers conclude that there are likely to be many missed opportunities to identify language difficulties within the health care and criminal justice and education systems. They propose that speech and language services should have a greater role in the youth justice system to facilitate early identification and support for those at risk of engaging in offending behavior.”

One publication of special assistance to me in my journey to create awareness of the impact of language disabilities on children who have experienced trauma, as well as those who need social-emotional learning (SEL) for other reasons, is Cole, S. JD, M.Ed (2005) Helping traumatized children learn (Massachusetts Advocates for Children: Boston).

This book has accompanied me on all workshops since its publication! I mention it in the workshops and recently have noticed an increase in workshop participants looking through its contents.

Within the book, there are many important sections. The one entitled “The Flexible Framework: An Action Plan for Schools” contains a subsection entitled “Language-Based Teaching Approaches.” This section notes that many of these students lose track of classroom activity, which may trigger anxiety, which “throws the student further off and makes it harder to catch up.” Language-based teaching strategies “are effective for reducing fear and increasing the ability to take in and learn information and follow rules.” The “how-to” paragraphs are as follows. Use of SGM® and Braidy the StoryBraid® facilitates each one:

Within the book, there are many important sections. The one entitled “The Flexible Framework: An Action Plan for Schools” contains a subsection entitled “Language-Based Teaching Approaches.” This section notes that many of these students lose track of classroom activity, which may trigger anxiety, which “throws the student further off and makes it harder to catch up.” Language-based teaching strategies “are effective for reducing fear and increasing the ability to take in and learn information and follow rules.” The “how-to” paragraphs are as follows. Use of SGM® and Braidy the StoryBraid® facilitates each one:

- Using multiple ways to present information to “reduce the fear evoked when chunks of information have been missed.”

- Processing specific information: pre-teaching new vocabulary and concepts, using guided questions centered on outcomes/consequences, emphasizing and repeating event sequences and causal relationships in life and texts. “Language therapists recommend giving examples that range from the concrete to the abstract, and they suggest using graphic organizers and physical manipulatives (maybe SGM®/Braidy®) to help children stay on track.”

- Identifying and processing feelings: “Children who have trouble using language to communicate emotions cannot always “formulate a flexible response” to situations and may react impulsively. Learning to identify and articulate emotions will help them regulate their reactions…Some children have cognitive profiles that interfere with their capacity to put words to feelings; they may need specialized approaches and the help of language therapists who work closely with mental health clinicians.” How about Braidy the StoryBraid® or the SGM® as part of this necessary intervention?

-

Organizing narrative material: “A child’s successful completion of many academic tasks depends on the ability to ‘Bring a linear order to the chaos of daily experience.’” Traumatic experiences can inhibit this ability to organize material sequentially, leading to difficulty reading, writing and communicating verbally.

Think about the Developmental Sequence of Narrative Abilities (MindWing Concepts) to foster this sequential memory ability as well as causal connections through language and children’s literature.

This cause/effect connection was noted in the text: Living in “circumstances that do not allow children to make connections between their actions and the responses they trigger can be left wary of the future, which feels to them both unpredictable and out of their control.” Thus, tools that focus on making these connections in literature and life may be extremely helpful.

Conclusion:

Often young children are asked to retell as part of their reading comprehension instruction. Many cannot retell the content, but can answer “comprehension questions” and are thus deemed OK! This prompting, while a necessary part of reading comprehension instruction, is not enough for many of our students who feel vulnerable (poverty, trauma, etc.)

Difficulties in this Question vs re-tell/tell area signal a need to develop the oral language for storytelling to be used academically and also for the extremely important area of interpersonal and intrapersonal communication. In fact, this problem is the very reason for the creation of the SGM® approach over 25 years ago at a school for students with dyslexia and language/learning disabilities. Narrative ability is a vital part of the connection! Using our Critical Thinking Triangle in Action® and other tools, we are here to help build this necessary language competency.

Please see:

Hughes, N. et al (2012) Nobody made the connection; the prevalence of neuro disability in young people who offend. London: Office for the Children’s Commissioner.

Hughes, N. et al. (2917) Language impairment and comorbid vulnerabilities among young people in custody. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 58 1106-1113. Doi:1111/jcpp.12791.

References that have proven useful to me as I continue to develop these tools:

The following articles are very important as a foundation:

Armstrong, J. (2011). Serving children with emotional behavioral and language disorders: A collaborative approach.

Snow, P. & Powell, M. (2005) What’s the story? An exploration of narrative language abilities in male juvenile offenders. Psychology, Family & Law, 11, 239-253.

Snow, P. (2009). Child maltreatment, mental health, and oral language competence: Inviting speech-language pathology to the prevention table. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(2), 95-103. Doi:10.1080/17549500802415712.

Snow, P., & Powell, M. (2002). The language processing and production skills of young offenders: Implications for enhancing prevention and intervention strategies. Report to Criminology Research Council.

Stanford, S. (2019) Juvenile Injustice. Leader Pubs: American Speech/Language and Hearing Association.

Books:

Cain, K. & Oakhill, J. Children’s comprehension problems in oral and written language: A cognitive perspective.

Cole, S. JD, M.Ed (2005). Helping traumatized children learn. Massachusetts Advocates for Children: Boston. (This has accompanied me on all workshops since its publication!

Hwa-Froelich, D. (Ed) (2015). Social Communication Development and Disorders. NY: Psychology Press (ADHD, Maltreatment, Social-Emotional Behavioral Disorders, etc.)

Levin, D. (2003). Teaching young children in violent times: Building a peaceable classroom. Cambridge, MA: NAEYC & Educators for social responsibility.

Van Der Kolk, B. M.D. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. NY: Penguin

Westby, C. & Culatta, B. (2016). Telling tales: Personal Event Narratives and Life Stories. ASHA: Language, Speech and Hearing Services in the Schools (LSHSS)

QUOTE:

“What is new is that trauma researchers can now explain the hidden story behind many classroom difficulties plaguing our educational system. Recent psychological research has shown that childhood trauma from exposure to family violence can diminish concentration, memory, and the organizational and language abilities that children need to function well in school. For some children, this can lead to inappropriate behavior and learning problems in the classroom, the home, and the community. For other children, the manifestations of trauma include perfectionism, depression, anxiety, and self-destructive—or even suicidal—behavior.”

Streeck-Fisher, A., and van der Kolk, B. (2000). Down will come baby, cradle and all: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of chronic trauma on child development. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34: 903-918.Shields, S. and Cicchetti, D. (2001). Reactive aggression among maltreated children: The contributions of attention and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(4): 381-395.

We need to continue to make oral language (narrative) / social communication connections so that “Everyone will make the connection!”

Maryellen Rooney Moreau

Maryellen Rooney Moreau, M.Ed., CCC-SLP, is the founder of MindWing Concepts. She earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in Communication Disorders at University of Massachusetts at Amherst as a Commonwealth Honors Scholar, and a Masters of Education in Communication Disorders at Pennsylvania State University. Her forty-year professional career includes school-based SLP, college professor, diagnostician, and Coordinator of Intervention Curriculum and Professional Development for children with language learning disabilities. She designed the Story Grammar Marker® and has been awarded two United States Patents. She has written more than 15 publications and developed more than 60 hands-on tools based on the SGM® methodology. Maryellen was awarded the 2014 Alice H. Garside Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Dyslexia Association, Massachusetts Branch.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.